Chef Werner Futterer and the traditions of great hotels

Fresh peas and carrots were interspersed with the smallest white pearl onions, all carefully seasoned. There was a choice of baked potatoes or baked potato skins. Hot rolls and butter were also included. The newspaper reported that the entree for the evening was “chicken a la Werner – it was flawless, the skin had the crispiness of a raw apple in the fall”.

The history of seaside resorts is often told in terms of famous visitors and famous residents. But what makes a real resort are the workers who provide a festive holiday experience for guests and residents. One of those industrious souls, who worked honorably in desert hospitality for decades, is worth stopping to remember.

Just over a week ago, Werner Futterer, the last of Palm Springs’ heyday’s top executive chefs, passed away quietly. Coming from a distant world in Europe, he had started his desert career with a bang at the El Mirador Hotel, today the very site of the Desert Regional Medical Center, where he poetically ended the journey of his life. .

Its presence in the desert has been loudly proclaimed as a boon to all who love to eat. His arrival made the paper: “Oilman Ray Ryan’s El Mirador hotel has announced the appointment of a new executive chef – with a twist. Werner Futterer, 32, is now one of the youngest top caterers at a major American hotel… Manager Gethin Williams called him “energetic and well beyond his years of experience”.

Hailing from a medieval town near Germany’s Black Forest, Futterer apprenticed in Switzerland after World War II, training at various restaurants, sanatoriums and hotels while attending culinary school. As was common in the food industry then (and still is today), opportunities presented themselves.

While working at the Hotel Gotthard along the Limmat River, crossed by many arched bridges in Zurich, he met a chef who was looking for a Swiss-trained cook to work in Stockholm. Together they left by train, but Futterer did not have the necessary papers when he arrived at the border. The young cooks were held up at the border until the chef called the police and they were finally admitted to Sweden.

Futterer found a job as assistant chef at the Grand Hotel in Stockholm, but Sweden was an extremely expensive place to live and would not be his last stop. His paternal aunt sponsored his immigration to the United States. On December 9, 1957, he boarded a Swiss Air DC 7 propeller plane. The flight took him from Zurich to Cologne, Germany, Shannon, Ireland, Newfoundland, Halifax, New -Scotland and finally New York.

Working at the Buffalo Club in his aunt’s hometown, he met Art Fri, who was a master at a hotel in Palm Springs. Futterer interviewed him and got the job in the remote desert.

In 1959, a cross-country road trip brought him to the El Mirador as “chef garde manger”, under fellow German Gerhard Knack. Literally a world away from Germany, he settled in the desert, becoming an integral part of the community.

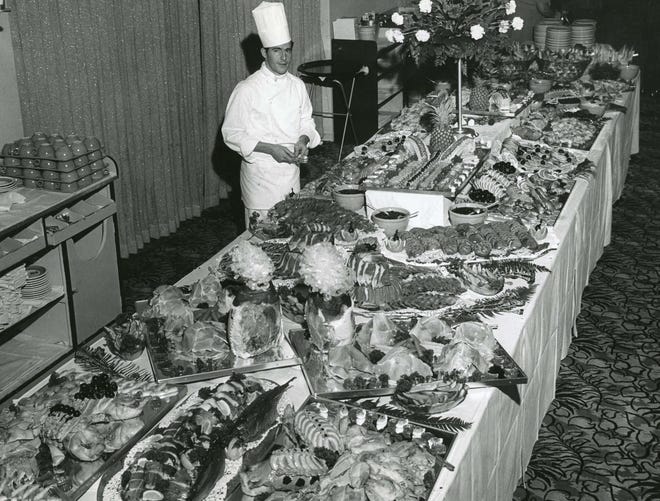

In 1965, with Knack’s retirement, Futterer was appointed executive chef of the entire El Mirador kitchen operation. His European training and sensitivity were highly prized. As desert visitors became increasingly sophisticated, there was a strong demand for haute cuisine to accompany swimming pools, golf courses, tennis courts, and nightclubs. Futterer would command a small army of cooks in order to support the legions of hotel guests and locals who wanted to dine on his cooking.

With the conversion of El Mirador into what was then called the Desert Hospital, Futterer became executive chef at the Spa hotel. His mouth-watering menus were published in the newspaper due to intense interest. Appetizers began the offerings, then “fresh fish of the day – white fish, sand dabs and salmon – as well as chicken, veal and lamb dishes” all dressed in secret European sauces were available. Tuna salad, Louie shrimp, pastries, soups and stews round out the menu. The tables were also always set with a bowl of relish of crunchy celery, carrots and large ripe green and black olives to accompany the ubiquitous pre-dinner cocktail.

Le Soleil du Désert has reproduced its recipes. For Marengo Veal Saute with browned onions, baby tomatoes, heaps of mushrooms, white wine and lots of butter, the instructions concluded: “Lay the veal out on a serving platter, pour the sauce over the top and garnish with parsley. chopped or sprigs. Sprinkle fried croutons around the meat.

No matter the cuisine, in the summer, hotels and restaurants close due to the extreme heat. Workers were forced to travel to find work elsewhere. In a kind of great pilgrimage across the valley, they found work in the seaside resorts, those whose seasons were opposite to those of the desert. They’ve spread to Yosemite, Lake Tahoe, coastal towns, and even farther afield in California. Futterer worked at the Stanley Hotel in Estes, Colorado, and in Harbor Springs, Michigan, always finding his way back to the desert for the winter season.

During his life in the desert, Futterer worked at the La Quinta Hotel, Mission Hills Country Club, Tamarisk Country Club, El Dorado Country Club, Rim Rocks Restaurant and Tennis Club, often as a chef guest or replacing friends and lending a hand. if necessary.

The Desert Sun noted in 1983, two decades after his tenure in the valley, “Chef Werner Futterer may have the distinction of being the only chef in the entire desert who does not eventually want to open his own restaurant. As executive chef of the Spa Hotel, Futterer has found a peace of mind in him that he doesn’t want to waste by taking on the responsibilities of his own establishment.

The article quoted him as saying, “’I would never open my own house…. Ten to twelve hours of work a day is already more than enough for me. It’s too hard to open your own place, especially in this city where restaurants open and close in the blink of an eye.

Futterer had indeed found happiness and a real home in the desert, working diligently in the biggest hotels in the valley. He understood the hard work and complicated logistics to create a memorable vacation for visitors. Trained in the old tradition of the greatest European hotels, the sober and elegant man has embodied this tradition for decades.

His passing not only marks the end of his long journey, but the end of an era.

Tracy Conrad is president of the Palm Springs Historical Society. The Memories Thanks column appears on Sundays in The Desert Sun. Email him at [email protected].

Comments are closed.